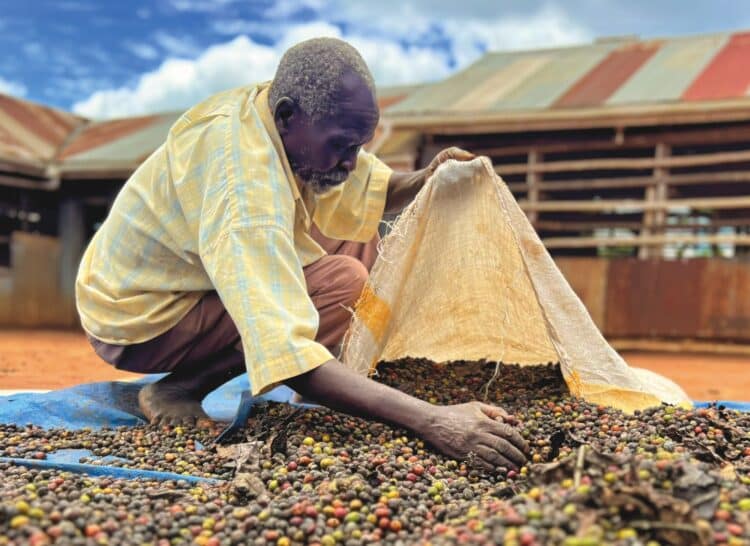

Coffee farmers and workers are the first link in a global value chain worth hundreds of billions of dollars. With the industry only projected to become more valuable, is enough being done to protect farmers’ health?

The global coffee industry is estimated to be worth somewhere north of US$200 billion per year, with expectations it will soar above US$300 billion in the next decade.

It’s the cornerstone of some national economies and, despite impacts from headwinds including rising prices and geopolitical tensions, demand for coffee only continues to grow.

Without coffee farmers and workers, this valuable international supply chain would teeter, then topple. With the average age of the farmer rising and key harvests falling or plateauing, is enough being done to improve the health of farmers to help secure coffee against increasing demand?

Safety is no accident

One of the biggest risks of injury or poor health to anyone who works in agriculture is the workplace itself.

The International Labour Organization is targeting the improvement of coffee farmer welfare through its Vision Zero Fund (VZF), with occupational health and safety (OSH) at the forefront of its programs.

Global Programme Manager for VZF Ockert Dupper says many of the hazards that are present in coffee farming are manageable and preventable.

“Coffee production often involves informal, small-scale farms where workers are especially vulnerable – they face a wide range of occupational hazards. Among the most common are what we call ‘ergonomic hazards’, often linked to repetitive tasks and heavy lifting,” says Dupper.

“Many coffee producers and workers report chronic back pain caused by carrying coffee sacks – sometimes larger than their own body size – multiple times a day.

“We often ask workers to identify the parts of the body they use most for work and the areas where they experience pain. Unsurprisingly, the two often overlap – a clear sign of the physical toll the work producing coffee takes and the urgent need for the implementing OSH management systems at the workplace level.”

Other common risks found in coffee production include chemical hazards due to the handling of pesticides and other agrochemicals, biological hazards such as snake bites, physical hazards such slips and falls often linked to uneven terrain, and mechanical hazards from using tools such as machetes or farm machinery.

Dupper says workplaces that focus on implementing OSH improvements help create safer working environments, which improve productivity and efficiency.

He cites positive impacts VZF has seen in major coffee producer Vietnam, as well as new interventions in Brazil and Uganda, as evidence of desire within the industry to improve health and safety outcomes.

“OSH is often perceived as a cost when it is, in fact, an investment. In Vietnam, ongoing efforts have led to more than 1700 OSH improvements across more than 460 farms. These include enhanced workstation layouts, safer storage and use of farm tools, improved machinery and electrical practices, and increased vehicle safety,” he says.

“This year we released two fact sheets that explore how coffee cooperatives can play a larger role in promoting OSH and upholding other fundamental principles and rights at work in Brazil and Uganda.

“There is also a toolkit that compiles more than 20 methodologies and tools produced by VZF for tackling OSH deficits at various levels of the supply chain, and a Collective Action Kit that presents activities and resources that each stakeholder can use to improve OSH.”

In pursuit of equity

Between 20 and 30 per cent of coffee farms around the world are believed to be operated by women, in some regions that figure soars – despite men typically having greater access to land, credit, and resources.

“Our research indicates women are playing an increasingly prominent role in the coffee sector, with the International Coffee Organization estimating they comprise up to 70 per cent of the workforce,” says Dupper.

“However, their contributions often remain invisible, and many face a double burden: working long hours in the field followed by unpaid caregiving responsibilities at home.”

Through her work as a photographer travelling through Latin America, Lucia Bawot has identified this double burden as actually being a triple burden. She has since created SANA, a social enterprise targeted at supporting the mental health and wellbeing of women coffee farmers and pickers in Colombia.

“I’ve been working in the coffee industry for the past 12 years and have had the opportunity to engage with more than 500 coffee families,” says Bawot. “In 2019, I decided to create a book I could leave as my own voice in this industry. I called it We Belong: An Anthology of Colombian Women Coffee Farmers – it’s dedicated to Colombia’s women coffee farmers.

“These women, for the most part, juggle a lot of roles. Many farmers, and women in general, suffer from time poverty. They perform nearly 70 per cent of farm labour – often unrecognised and unpaid – while facing other systemic inequities like gender-based violence, limited land ownership, and the triple burden of caregiving, household duties, and farm work.”

According to the WHO Atlas 2024, most Latin American nations contribute less than two per cent of their health budgets to mental health, with much of that sliver concentrated in urban areas. To remove this roadblock, Bawot has made SANA’s programs fully online and accessible by mobile.

“We provide an integrative five-month program focused on mental health and wellness that combines several interventions from tele-therapy sessions, virtual education, and community-based support,” she says.

“We meet women where they are, offering accessibility and tailored care so they can strengthen their emotional wellbeing to live healthy and more fulfilling lives.”

The program’s launch in Colombia has been a success. Bawot reported a 100 per cent attendance rate in its pilot, with 82 per cent of women stating they would like to do the program again.

She says there are plans to solidify

SANA’s presence in Colombia before potentially taking it to other Latin American nations.

“Our idea is to reach 120 women coffee farmers in Colombia, with the goal of piloting programs in other countries next year,” Bawot says. “Currently, we have 66 women enrolled in six active cohorts from Nariño, Huila, Santander, Antioquia, Risaralda, and Tolima. To date, we have completed more than 232 teletherapy sessions and have sent more than 266 wellness and mental health content pieces.

“We have some traction with associations in Costa Rica and Mexico. This support should not only be for Colombian coffee farmers and pickers. It should reach other countries and other origins.”

Bawot believes the early success of SANA’s program showcases a need for mental health in farmers to be prioritised, because without putting them in a position to thrive the whole industry will be at risk.

“I don’t know if in the coffee industry we are prioritising the wellbeing of the farmers,” she says.

“I still believe for the most part we care more about climate change. We see it from a perspective of ‘we won’t have coffee plants or coffee to drink’, but if we don’t have people to tend to the land that produces coffee it doesn’t matter how much money you invest in different agricultural practices, you still won’t have coffee.

“If we’re not mentally and emotionally well it doesn’t matter how much coffee we can sell, because we won’t have the energy, motivation, or clarity to excel in our roles.”

Seeing is believing

Sometimes, the simplest solutions can be the most powerful. A pair of eyeglasses can change someone’s world, and it is VisionSpring’s mission to provide access to them for people in some of the world’s most remote communities.

The not-for-profit conducts significant work in the coffee and tea growing regions of Asia and Africa, and has seen significant boosts in productivity and quality of life through its work.

In fact, the provision of eyeglasses has been found to be the most powerful enhancer of productivity of any medical intervention, according to Anshu Taneja, the Managing Director of VisionSpring Foundation in India.

“In 2018 we did a detailed study in partnership with Amalgamated Tea Plantations, Queen’s University Belfast, Orbis, and Clearly,” says Taneja. “We found the productivity increase in tea pickers and tea sorters who were given eyeglasses was anywhere between 22 to 32 per cent.

“Coffee farming is a similarly intuitive practice: it’s very vision intensive work. I believe if we did the same study in coffee we would see similar results.

“There’s potential for a very high positive economic impact on the work these people do, but also huge potential to improve quality of life and reduce instances of injury while working.”

VisionSpring, while active around the world, has a significant presence in the plantations of India. Overall, it has fostered the provision of more than 14 million pairs of glasses since its foundation in 2001.

“In India, through our mission, we typically screen between two to three million people annually and provide 1.2 million pairs of glasses per year,” says Taneja.

“One of our key programs is called Livelihoods in Focus. We go into tea and coffee growing regions around the world and take screenings and glasses to them.

“Our goal is to reach 200,000 tea and coffee workers in India in the next couple of years, and much of that will be in regions such as West Bengal, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, and Karnataka.”

As people age, their vision tends to become worse due to a natural condition called presbyopia, which can be easily managed with a simple pair of reading glasses.

With the average age of the coffee farmer continuing to rise, Taneja believes VisionSpring’s mission will only become more important to maintain productivity in the industry.

“For many of the plantations we’ve seen, the younger generation is moving and getting involved in other work. Those who remain behind are getting past that boundary age of 40 where more people need glasses to see things up close,” he says.

“We started screening these workers and found high refractive error, with 65 to 70 per cent needing glasses. For coffee, 99 per cent of people who needed glasses had never worn them.”

Taneja says investing in programs that can boost the wellbeing of farmers has the potential to become a critical part of the coffee supply chain.

“We have committed to going into all the tea and coffee plantations in the regions we’re working to make them ‘Clear Vision Estates’. That would result in an enormous increase in productivity and efficiency, but also the quality of life and general wellbeing of the worker,” he says.

“I believe there is a moral responsibility to invest in the wellbeing of the workers. This is a very low cost, high impact intervention that can make the whole supply chain more resilient.”

This article was first published in the November/December 2025 edition of Global Coffee Report. Read more HERE.