With coffee production yields in many key Latin American origins falling, how is Mexico bucking the trend with steady growth since its coffee leaf rust epidemic in the 2010s?

For decades, Central and South America have formed the bedrock of the world’s coffee production.

While in recent years Asian nations such as Vietnam and Indonesia have levelled up to become some of the world’s largest producers, Brazil and Colombia still combine to produce almost half of the world’s coffee, with neighbouring regions such as Peru, Honduras, and Guatemala contributing far from negligible amounts.

Overall, however, coffee production is falling in some of these key South American production regions. Frosts in Brazil have seen cascades in harvest projections, while climate change continues to impact yields in Central America.

One outlier in this region is Mexico. While far from immune from the issues influencing neighbouring nations, since rebounding from a coffee leaf rust disaster in the 2010s it is on a slow and steady growth trajectory, with key market indicators projecting a consistent annual growth rate of 0.5 per cent per year between 2024 and 2028.

Bouncing back from an epidemic

Coffee was first introduced to Mexico in the 18th century and over the next 100 years became a significant export crop. Today, the country’s coffee production is mainly based in the south’s mountainous regions – predominantly Chiapas, Veracruz, and Puebla – where the high altitudes, cooler temperatures, and well-distributed rainfall favour Arabica production.

“The majority of coffee from Mexico is grown in Chiapas, but we do quite a bit of work in Oaxaca and even Veracruz,” says John Cossette, Vice President of Royal Coffee, a United States (US) green bean importer that’s been active in the Mexican coffee industry for decades.

“Pretty much all we buy is Arabica, but there are certain places – Oaxaca in particular – that still have a lot of the older Arabica strains of coffee growing such as Typica and Bourbon. In Chiapas, the majority of coffees are modern hybrids.

“Some Mexican producers are even growing the Pluma varietal, which comes from coffee trees more than 50, 60, or 100 years old. They’re becoming less and less available because people are pulling them out of the ground, but we still have sources for these kinds of coffees.”

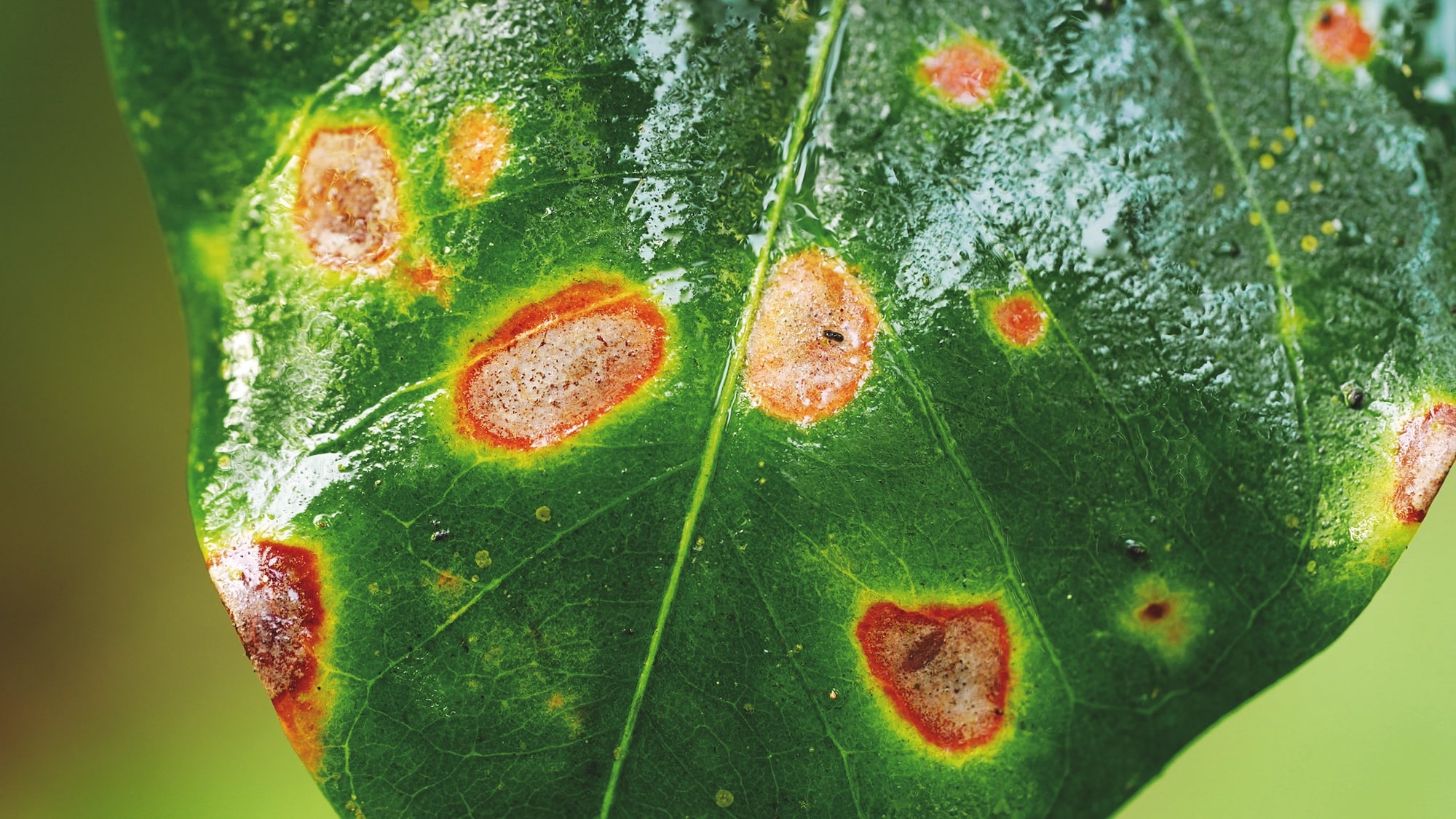

Since being first identified in Africa in the 19th century, coffee leaf rust – also known as Hemileia vastatrix or CLR – has spread to all coffee growing regions of the world, where it is estimated to cause billions of dollars of economic damage every year.

Mexico, along with the wider region of Central America, endured one of the worst CLR epidemics of modern times in the early 2010s. It is estimated up to 70 per cent of the region’s coffee plants were impacted by the fungal disease, which restricts the plant from photosynthesising and therefore leads to reduced yield, weakened plants, and in many cases plant death.

In Mexico, the worst of the epidemic was seen between 2012 and 2014. According to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), it caused the output in the 2013/14 harvest to drop by 700,000 60-kilogram bags. The lowest recorded harvest year was 2015/16 at an estimated 2.3 million bags.

“Chiapas, in particular, got hit pretty hard – especially in the lower areas where it funnels through from Guatemala. It was like a virus just sweeping through Central America. We had a farm we worked very strongly with for years that pretty much got wiped out,” says Cossette.

As the crisis worsened, the Mexican government worked with a number of NGOs to establish training programs with farmers to reduce the spread of the disease and set up breeding nurseries to supply them with disease-resistant coffee plants.

While it took three more years to overcome the ripple effects of the epidemic, the industry has now rebounded to pre-epidemic levels with the 2025/26 harvest forecast at 3.9 million bags.

Strong domestic demand

The majority of growers in Mexico are small family farms performing their own labour, or those who have access to labour in their own communities.

“The regions where coffee is grown are remote and rural, and not being replaced by real estate ventures or population incursions – something we see in other origins,” says Cossette.

“Mexico has a very strong domestic market and a demand for coffee that’s still growing, so in addition to their export market, they also have the ability to sell their coffee domestically which makes for a stable situation.”

Over the past couple of years, the Mexican Government has introduced a series of initiatives to support domestic coffee production. In 2024, it launched Café Bienestar, an instant coffee brand developed to support local coffee producers and remove intermediaries that could reduce their profits.

“We want to create a Bienestar brand that purchases directly from farmers at fair prices, processes the coffee, and offers it as instant coffee under this brand,” said Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum at the time.

What’s more, in April 2025 the government approved the Law for the Sustainable Development of Coffee Growing. This legislation is designed to strengthen the domestic coffee industry through training, research, quality improvement, financing, fair trade, and environmental sustainability to support farmers impacted by CLR and climate change.

The land of opportunity

Despite the strong domestic demand, the US is by far the largest consumer of Mexican coffee. The USDA reports a forecast estimate of 1.9 million 60-kilogram bags of Mexican coffee imported into the US for 2024/25, a small increase from the 2023/24 estimated total of 1.86 million bags.

“Most of our sales are to roasters in the Western US where we see strong demand for Mexican coffee. It’s popular in California in particular, but also in other regions such as Wisconsin, Illinois, and Minnesota,” says Cossette.

Lupita Sanchez founded Café Metzli in Los Angeles in 2022. Her business only sells Mexican beans and the name translates to ‘moon’ in a native language of the Latin American nation.

Michoacán, where she was raised, is not one of the major coffee-producing regions of Mexico. Yet, before her family moved to the US when she was a child, her father operated a farm.

Sanchez believes added transparency in dealing with producers has been key to elevating the standing of Mexican coffee in the export market.

“I always put the name of the producers or their farm and then the state it is grown in on the coffee,” she says. “I’m super transparent with them. They know how much I sell their coffee for. Now, three of the producers I brought to the US for the first time are selling their coffee to places such as Japan and South Korea.

“Producers like Rancho El Separo in Veracruz, and Director al Origen from Puebla, have grown to rank in the top 10 in Cup of Excellence. I have such a beautiful relationship with my producers, and every year my volume grows.”

Sanchez says in her time operating Café Metzli, she’s seen a huge increase in interest in Mexican specialty coffee.

“When I started, I would estimate about one in 15 specialty coffee shops had Mexican coffee. It wasn’t really a thing and I couldn’t understand why – it was close to the US, so I assumed it would be cheaper and easier to get,” she says.

“People are now learning that Mexican coffee exists. Five years ago, a lot of the coffee shops would say the coffee was from Colombia or Guatemala, but in fact it was from Mexico and they were lying, which is really sad.

“But the new generation of coffee drinkers is pushing for change in the industry, and they’re more attuned to specialty coffee and where it is produced, and Mexican coffee is really starting to shine.”

Demand for Mexican coffee in its leading export market of the US has reportedly surged this calendar year as a result of President Donald Trump and the Republican Government’s ‘Liberation Day’ tariffs on a range of coffee producers.

Brazil, where the US imports most of its coffee from, has been hit with tariffs as high as 50 per cent between April and October, while other major producers including Vietnam, Indonesia, and Colombia have also seen tax hikes.

Cossette says, at least for those few months, the Mexican coffee industry has benefitted from the higher rates being imposed on other origins.

“The country that has benefitted the most out of this is Mexico, because at this point it’s the only coffee-producing country that is not being tariffed. That has markedly escalated demand this year.

“It’s been an easy decision for us to buy Mexican coffee, and buy as much as we can. Fortunately, we have longstanding relationships so it hasn’t been a huge challenge for us to do so.”

Sanchez sees major opportunities in the community that is being built around Mexican coffee production, and the free knowledge sharing she sees among the producers she works with.

“When I first bought coffee from La Salitas, they were scoring around 83 or 84. Now a lot of it is around 85 or 86. They’re putting so much love and passion into what they do, and they’re not being greedy or selfish with information to help those around them grow better coffee,” she says.

“It’s beautiful to see the community working together and putting so much love into it, and they’re teaching their children to grow coffee when they get home from school. I’ve seen 10-year-olds learning how to cup coffee.

“Some of my producers, their grandfather was the owner of the rancho, which is now run by the grandchildren. Coffee is continuing through generations in Mexico, and that’s super important.”

This article was first published in the November/December 2025 edition of Global Coffee Report. Read more HERE.